Week 3: Robotics + Art

Since the dawn of

industrialization, what we perceive as art has changed dramatically, thanks

ultimately to mechanization. The

explosion of personal computers and Moore’s Law in the latter half of the 20th

century further drove mechanization and computation to set the stage for a new

type of masterpiece: robotics (Intel.com).

|

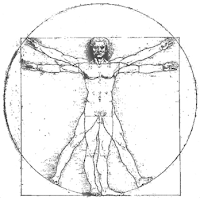

| Vitruvian Man |

What was once

reserved for sculptures and paintings, humanoids became a new focus of

idealized beauty. During the

Renaissance, artists such as Leonardo da Vinci focused on this idealized,

perfect human form, as seen in his Vitruvian Man; but recently, humanoid

designers have taken up this focus on realistic human idealization (Stanford.edu). Dr. Dennis Hong, Professor of Mechanical and

Aerospace Engineering at UCLA, has succeeded in this blending of art and

science into CHARLI, “the United States’ first full-size autonomous human

robot” (Hong). CHARLI is able to walk in

any direction, as well as kick, and perform several upper body tasks. On top of all this, CHARLI is aesthetically

pleasing to look at, and includes this idea of human beauty within robotics.

|

| CHARLI |

|

| Iron Man |

Another great

example of this idea of blending an aesthetically pleasing robot in an

idealized human form can be seen in the Iron Man movie series. The Iron Man suit contains hundreds of “bells

and whistles”, but does all of this in the form of a very large and muscular

idealized human body.

While the

increased mechanization and computing capabilities have made this new art form

of robotics possible, some have argued that it has ultimately taken the

originality out of art. Walter Benjamin,

in his “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, argues that mechanization

has allowed for art to be reproduced so closely to its original form that there

is no distinction between the real and reproduced; besides the fact that the

original work includes the aura of the culture and time. This mechanical reproduction ultimately

destroys the authenticity of the art as the “unique existence” of the original

work becomes lost (Benjamin). Douglas

Davis continues upon Benjamin’s work, further expanding on the idea that

mechanization and computing has devalued, rather than enhanced, art (Davis).

References:

“50 Years of Moore's

Law.” Intel, 2015, www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/silicon-innovations/moores-law-technology.html.

Accessed 21 Apr. 2017.

Benjamin,

Walter. “The Work of Art in the

Age of Mechanical Reproduction”. 1936.

Davis, Douglas. “The

Work of Art in the Age of Digital Reproduction (An Evolving Thesis: 1991-1995).” Leonardo,

vol. 28, no. 5, 1995, pp. 381-386.

Hong, Dennis.

“CHARLI: Cognitive Humanoid Autonomous Robot with Learning Intelligence.” RoMeLa,

UCLA, 2017, www.romela.org/charli-cognitive-humanoid-autonomous-robot-with-learning-intelligence/.

Accessed 21 Apr. 2017.

“Leonardo's Vitruvian

Man.” Stanford History, 2017,

leonardodavinci.stanford.edu/submissions/clabaugh/history/leonardo.html.

Accessed 21 Apr. 2017.

Comments

Post a Comment